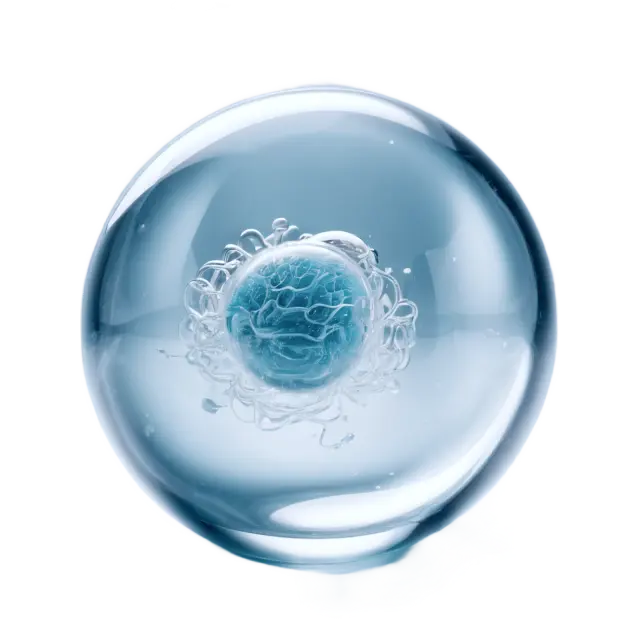

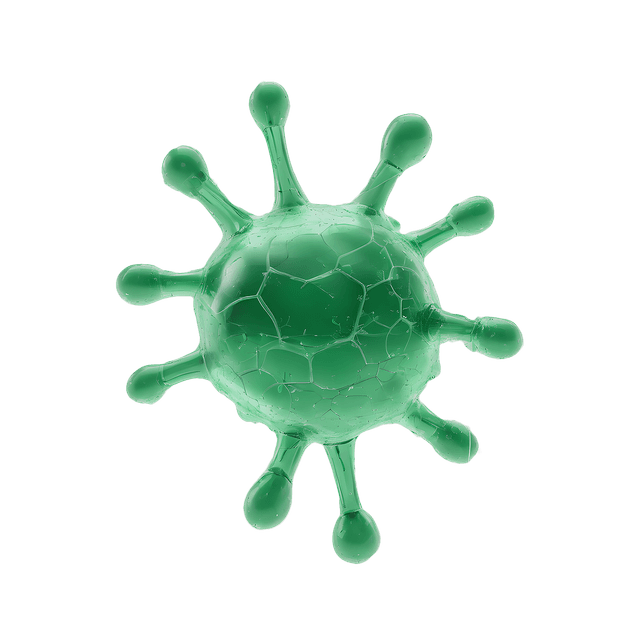

Bacteroides vulgatus

Gut health is a hot topic in medical research, and one of the bacteria that has received much attention is Bacteroides vulgatus. This bacterium has shown both positive and negative effects on our health. In this article, we will focus on why it may be desirable to reduce levels of Bacteroides vulgatus in the gut, especially if you suffer from certain health issues.

Bacteroides Vulgatus and the Gut Mucosa

The gut mucosa is covered with a layer of protective mucus that shields against harmful substances and microorganisms. According to several scientific studies, Bacteroides vulgatus has the ability to break down this protective mucus layer (1-6). Although this does not necessarily mean health problems for everyone, it can be problematic if you have high levels of these bacteria along with symptoms such as gas, abdominal pain, and cramping.

Scientific Evidence

Study 1: A 1989 study showed that Bacteroides vulgatus can break down intestinal glycoproteins (1).

Study 2: Another study from 1977 found that these bacteria can ferment mucin and plant polysaccharides (2).

Study 3: A review article from 2010 discussed interactions between mucin and bacteria in the human digestive system (3).

Link to Inflammatory Conditions

Higher levels of Bacteroides vulgatus have also been associated with inflammatory conditions such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. These conditions negatively affect the gut mucosa and can be worsened by the presence of these bacteria.

Ulcerative Colitis: A study showed that high levels of Bacteroides vulgatus could induce ulcerative colitis in animal models (7).

Crohn's Disease: Several studies have linked high levels of Bacteroides vulgatus to Crohn's disease (8-11). These bacteria are thought to hinder mucosal healing (12).

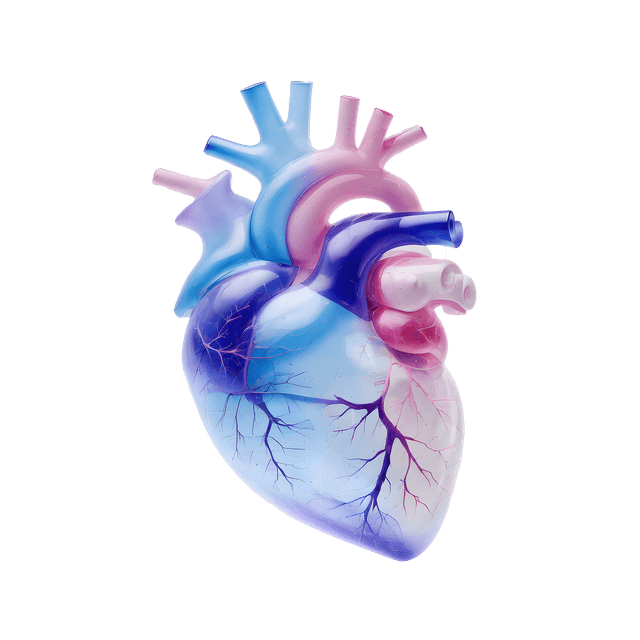

Link to Metabolic Diseases In addition to inflammatory bowel diseases, higher levels of Bacteroides vulgatus have also been linked to pre-diabetes and type-2 diabetes (13, 14).

Type-2 Diabetes: A 2016 study showed that the presence of these bacteria negatively affects the host's serum metabolome and insulin sensitivity (14).

Practical Advice for Reducing Bacteroides Vulgatus

Dietary Changes A balanced diet rich in fiber can help reduce levels of Bacteroides vulgatus. Fiber promotes the growth of beneficial bacteria that outcompete the harmful ones.

Tips:

Eat more fiber: Include fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes in your diet.

Avoid processed foods: Processed foods can promote the growth of harmful bacteria.

Probiotics and Prebiotics Probiotics are live microorganisms that can benefit your health when consumed in adequate amounts. Prebiotics are substances that promote the growth of beneficial bacteria.

Tips:

Probiotic-rich foods: Yogurt, kefir, and sauerkraut.

Prebiotic-rich foods: Onions, garlic, bananas, and asparagus.

Medical Treatment In some cases, medical treatment may be necessary. Always consult a doctor before starting any form of treatment.

Tips:

Antibiotics: Can be used to reduce specific bacterial populations.

Anti-inflammatory drugs: Can be used to treat inflammatory conditions.

Conclusion

Reducing levels of Bacteroides vulgatus in the gut can offer several health benefits, especially if you suffer from inflammatory bowel diseases or metabolic diseases like type-2 diabetes. By making dietary changes, using probiotics and prebiotics, and consulting a doctor if needed, you can improve your gut health.

Scientific References

Ruseler-van Embden, J. G., van der Helm, R., & van Lieshout, L. M. (1989). Degradation of intestinal glycoproteins by Bacteroides vulgatus. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 49(1), 37–41.

Salyers, A. A., Vercellotti, J. R., West, S. E., & Wilkins, T. D. (1977). Fermentation of mucin and plant polysaccharides by strains of Bacteroides from the human colon. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 33(2), 319–322.

Derrien, M. et al. (2010). Mucin-bacterial interactions in the human oral cavity and digestive tract. Gut Microbes, 1:4, 254–268.

Png, C. W. et al. (2010). Mucolytic Bacteria With Increased Prevalence in IBD Mucosa Augment In Vitro Utilization of Mucin by Other Bacteria. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 105:11, 2420–2428.

Hoskins, L. C. et al. (1992). Mucin Glycoprotein Degradation by Mucin Oligosaccharide-degrading Strains of Human Fecal Bacteria. Microbial Ecology in Health and Disease, 5:4, 193–207.

Tailford, L. E. et al. (2015). Mucin glycan foraging in the human gut microbiome. Frontiers in Genetics, 6, 81.

Onderdonk, A. B. et al. (1981). Production of experimental ulcerative colitis in gnotobiotic guinea pigs with simplified microflora. Infection and Immunity, 32:1, 225–31.

Saitoh, S. et al. (2002). Bacteroides ovatus as the predominant commensal intestinal microbe causing a systemic antibody response in inflammatory bowel disease. Clinical and Diagnostic Laboratory Immunology, 9:1, 54–9.

Rath, H. C. et al. (1999). Differential induction of colitis and gastritis in HLA-B27 transgenic rats selectively colonized with Bacteroides vulgatus or Escherichia coli. Infection and Immunity, 67:6, 2969–74.

Lucke, K. et al. (2006). Prevalence of Bacteroides and Prevotella spp. in ulcerative colitis. Journal of Medical Microbiology, 55

, 617–624.

Ó Cuív, P. et al. (2017). The gut bacterium and pathobiont Bacteroides vulgatus activates NF-kB in a human gut epithelial cell line in a strain and growth phase dependent manner. Anaerobe, 47, 209–217.

Fujita, H. et al. (2002). Quantitative analysis of bacterial DNA from Mycobacteria spp., Bacteroides vulgatus, and Escherichia coli in tissue samples from patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Journal of Gastroenterology, 37:7, 509–516.

Leite, A. Z. et al. (Year). Detection of Increased Plasma Interleukin-6 Levels and Prevalence of Prevotella copri and Bacteroides vulgatus in the Feces of Type 2 Diabetes Patients. Frontiers in Immunology.